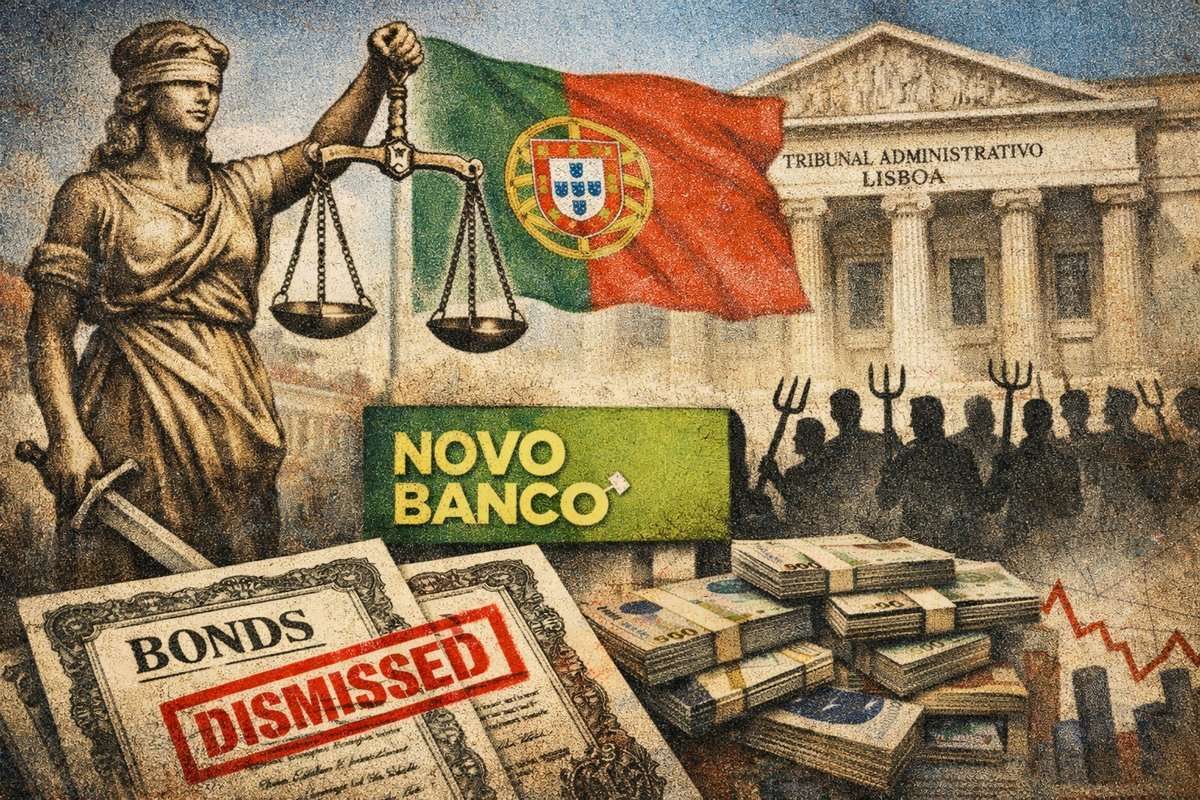

Lisbon court upheld the Bank of Portugal’s 2015 Novo Banco bond retransfer—retail investors protected, institutional holders hit. Appeals are now underway

Nearly a decade after Portugal’s central bank pushed roughly €2 billion of senior bonds out of Novo Banco and back into the wreckage of Banco Espírito Santo (BES), the Lisbon District Administrative Court has now delivered the first major trial-court ruling in the fast‑tracked “pilot cases” — and it sides decisively with the state.

In a judgment issued by a three‑judge panel — António Gomes da Silva (rapporteur), Maria Carolina Duarte, and Ana de Campos — the court upheld the validity of the 29 December 2015 Bank of Portugal “Retransmission of Liabilities” decision and dismissed the investors’ actions on the merits, ordering the claimants to pay costs.

For bondholders who have spent years arguing that the “retransfer” was a retroactive, selective bail‑in dressed up as administrative housekeeping, the ruling is more than a legal defeat. It is a judicial endorsement of a stark policy choice: retail depositors and small investors were protected — and large, typically institutional holders were left to absorb the loss.

And that is exactly where law and politics blur.

A case engineered for speed — after years of delay

This outcome did not arrive through ordinary litigation. The Administrative Court’s president activated the procedural expediting mechanism in Article 48 of the Code of Procedure in Administrative Courts (CPTA), selecting four joined actions as pilot cases: 729/16.1BELSB, 730/16.5BELSB, 743/16.7BELSB, and 775/16.5BELSB.

The pilot-case structure was already controversial among investors. In a previous coverage, we described a process in which dozens of cases were bundled, then steered toward a handful of “test” files — and reported that the court moved toward deciding the merits without full hearings.

Now, with the pilot judgment in hand, what bondholders feared is becoming real: a single ruling, built on a narrow reading of the applicable law and deference to “financial stability,” threatens to shape the fate of many stayed or parallel cases.

Preliminary wins that turned into a substantive rout

Before reaching the merits, the court ruled on a set of procedural objections:

- It accepted the objection that claimants lacked standing to challenge the Perimeter and Contingencies resolutions (treating them as non-harmful or inapplicable to these plaintiffs).

- It rejected the argument that claimants lacked standing to challenge the Retransmission decision itself.

- It dismissed BES as a defendant, reasoning that BES did not have legal standing to be sued in this configuration.

- It rejected Novo Banco’s time‑bar defence, allowing the action to be heard on the merits.

Those points gave bondholders a brief opening — but the court ultimately rejected every substantive ground for annulment.

The core legal move: lock the case into the 2014 framework

The central pillar of the judgment is the court’s choice of which law governs the 2015 retransfer.

The plaintiffs built much of their argument around Article 145‑Q of the Portuguese banking framework (RGICSF), introduced via Law 23‑A/2015 (March 2015), claiming it imposed conditions and criteria that were not met. The court’s response: that version is not applicable.

The court reasons that:

- The BES resolution was adopted 3 August 2014, when the Bank of Portugal created Novo Banco and expressly reserved the ability to transfer or retransmit assets and liabilities between the two entities.

- When Law 23‑A/2015 entered into force (the court calculates 31 March 2015), it included transitional provisions — but none addressing retransfers flowing from resolutions adopted under the prior RGICSF.

- With no transitional rule, the court applies the general succession-of-laws principle under Article 12 of the Civil Code, concluding that the validity of the contested mechanism must be assessed under the 2014 frameworkconsolidated by the original resolution.

This is more than technical legal plumbing. It effectively means that post‑2015 safeguards cannot be used to attack a 2015 act if those safeguards were not part of the legal environment “baked into” the 2014 resolution.

For bondholders, this is the judgment’s most consequential choice — and the one most easily read as “state-protective.” If the later law had applied, the legal scrutiny could have shifted materially.

Even under the 2015 regime, the court says the 2014 wording was enough

The judgment does not stop at inapplicability. It goes further: even assuming Article 145‑Q applied, the court says the legal demand is minimal — essentially requiring only an express statement that retransfers may occur, not an itemised list of future liabilities or bespoke retransfer criteria.

The court points to the 2014 resolution’s express reservation that the Bank of Portugal “may at any time” transfer or retransmit assets and liabilities between BES and Novo Banco under Article 145‑H(5).

Investors had also leaned on Directive 2014/59/EU (the BRRD), arguing that EU law required specificity (“certain” assets/liabilities) in the resolution act. The court rejects that reading, stating that the directive’s language does not imply a requirement to pre‑identify the precise assets/liabilities that might later be retransferred; it is enough that the possibility of retransmission is provided for in the resolution act.

It also notes that, at the time of the 3 August 2014 resolution, the BRRD transposition period was still running; individuals’ ability to invoke direct effect was therefore not straightforward.

“Equitable” does not mean “equal”: the court approves picking losers

If the legal framework question is the key to the door, the equality analysis is what closes it.

The court emphasises that Portugal’s resolution regime requires equitable treatment of creditors, not strict equality among creditors of the same category — and it allows differentiated treatment if justified by public interest, proportionality, and non‑discrimination.

Then comes the most politically resonant part of the record: who was chosen and who was spared.

The court accepts that the Bank of Portugal selected five series of senior bonds based on criteria including that they were:

- originally issued to qualified investors (institutional segment),

- had a €100,000 unit denomination,

- and were “not typically targeted at small investors, even on the secondary market.”

By contrast, bonds with smaller denominations (e.g., €1,000/€2,000/€5,000) were viewed as retail-oriented instruments whose inclusion could threaten depositor confidence and Novo Banco’s stability — an outcome the resolution regime is designed to avoid.

The judgment also anchors this selection in the stated statutory goals of resolution, explicitly including financial stabilityand “safeguarding taxpayers and the public purse.”

This is the point where a purely legal dispute starts to look, unavoidably, like a distributional decision — the kind governments make, and courts typically hesitate to second‑guess.

Nationality discrimination: the court sees none — and warns against a “foreign shield”

Some plaintiffs argued the 2015 retransfer was discriminatory against non‑Portuguese holders. The court dismisses that claim, finding no nationality criterion in the decision and describing the selection rules as facially neutral (instrument type, investor profile, stability rationale).

Notably, the court adds a sharp counter‑argument: accepting the plaintiffs’ theory would imply that foreign investment funds could be “guaranteed” not to bear losses in a Portuguese resolution — a result the court treats as incompatible with the resolution framework.

“Not a bail‑in, not a liquidation”: the court frames the retransfer as compulsory corrective surgery

Bondholders have long said the 2015 decision was, in economic substance, a bail‑in targeted at a convenient subset of creditors. The court rejects that characterisation.

In its legal framing, the retransfer is the exercise of a retransmission power inherent to the bridge‑bank design: if liabilities transferred to the bridge bank are later found to exceed transferred assets, the Bank of Portugal can “at any time” retransmit to reconstitute the proper perimeter.

The court further states that allegations the retransfer was designed to improve Novo Banco’s financial position for sale are “unfounded,” saying the regime required the central bank to act once misallocation/overvaluation was detected.

It leans on the factual premise that impairments and losses emerging after 2014 reflected problems inherent in the BES assets transferred to Novo Banco — meaning the correction was not discretionary “engineering,” but a necessary alignment of assets and liabilities.

Yet the documents show the economic (and political) stakes

Even as the court rejects the “sale engineering” narrative, the record contains details that underline why investors suspect the state’s economic interest dominated the outcome.

A Novo Banco communication reproduced in the case materials states that the accounting entries resulting from the retransfer would have a positive impact on Novo Banco’s Common Equity Tier 1 ratio, “to around 13%,” and that the decision “protects all depositors.”

Those are not small effects. They go directly to the bank’s capital optics, market confidence, and the state-backed architecture standing behind the bridge bank.

Was this legal reasoning — or political insulation?

The structure and language of the judgment make one thing clear: the court views the investors’ interests as subordinate to the public objectives written into the resolution regime.

In one of the most striking passages, the court states that given the “extremely important public interest objectives at stake,” adopting the retransfer decision “could not be held hostage to the absolute safeguarding of investors’ positions.”

That sentence is legal — and unmistakably political in its implications.

Because it echoes what bondholders have argued since 2015: the state needed a clean balance sheet and social calm, and the simplest way to get it was to spare the many and charge the few.

Retail investors were spared, while large holders were targeted. This raise the question of whether authorities feared that small savers would “take to the streets with pitchforks.”

Today’s judgment doesn’t repeat that language. But it validates the underlying calculus by accepting, as legitimate, the choice to protect retail confidence and system stability — even when that means imposing exceptional losses on a narrower group of institutional creditors.

In other words: if it looks like a political compromise, the court has now explained why it is also legally permissible.

What comes next: appeal pressure, and a clock that does not stop

The decision is not necessarily the final word. Under Portugal’s administrative procedure, appeal deadlines are typically short — the CPTA’s general appeal rule is commonly referenced as 30 days from notification.

But for claimants in stayed or parallel actions, the practical reality is harsher: the pilot-case ruling sets a gravitational field. If investors want to avoid being passively bound by a precedent-like outcome, many will feel compelled to appeal — quickly, and at additional cost.

After ten years, the Lisbon court has delivered what bondholders call the opposite of justice delayed: justice denied — in a judgment that, by its own reasoning, places the protection of financial stability and the public purse ahead of institutional investors’ claims.

0 Comments