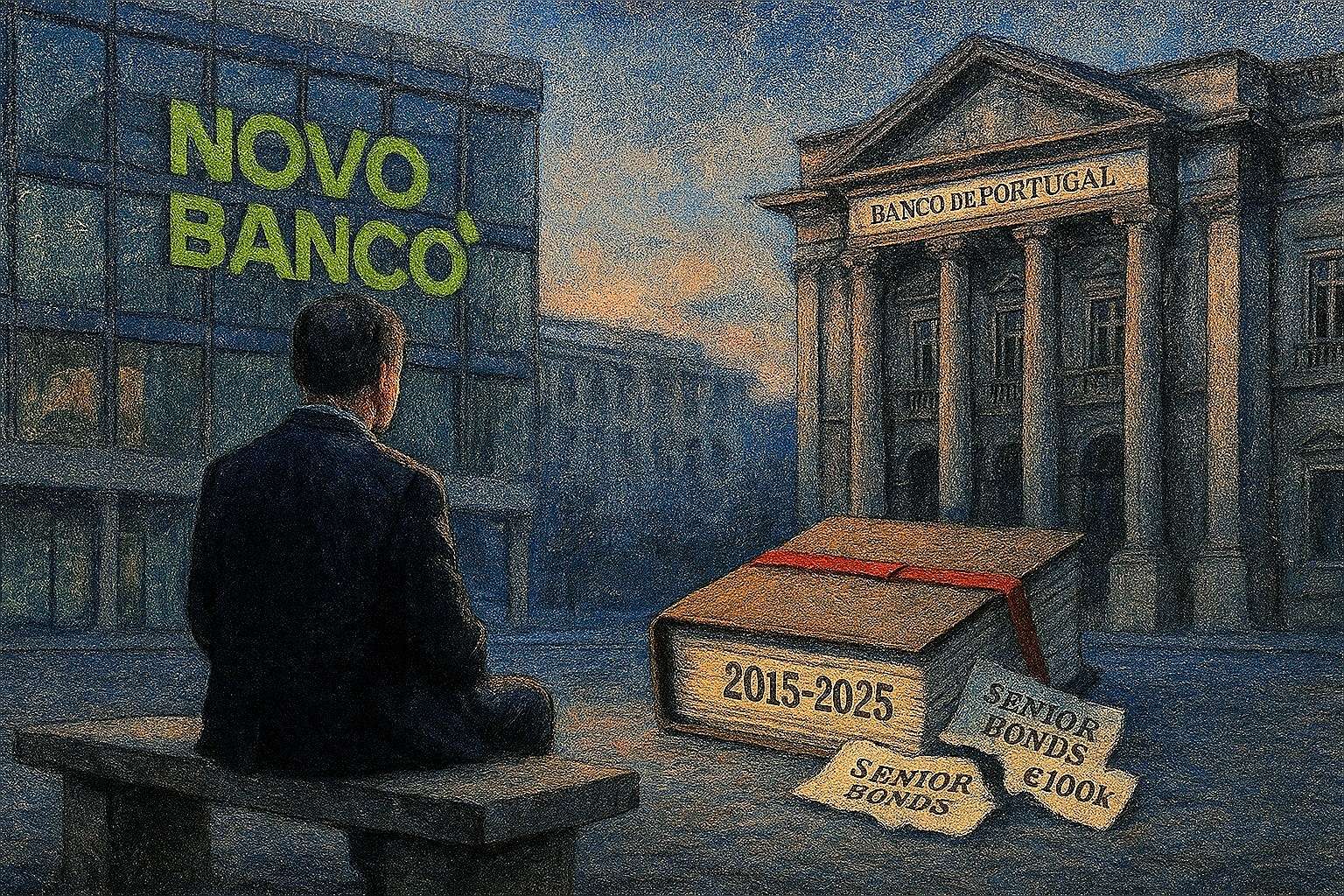

A decade of judicial silence, billions of euros vanished, international investors left unprotected. This is the story of Banco Espírito Santo (BES) and Novo Banco—an episode that lays bare serious cracks in Portugal’s court system and Europe’s promise of financial fairness

Ten years of adjourned hearings, institutional quiet, and one unanswered question: what became of justice for BES and Novo Banco bondholders? The rescue—marketed as an “orderly resolution”—vaporised billions, yet Portugal, in the heart of the EU, has still not produced a single first‑instance judgment on one of the most controversial post‑crisis financial events.

Summer 2014: The Fall of Banco Espírito Santo

In August 2014 the BES empire collapsed under hidden debt and murky ties to Espírito Santo Financial Group. The Bank of Portugal (BdP) invoked its domestic RGICSF framework because the EU Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) assumed a direct effect in the Portuguese jurisdiction only from 1 January 2015. A bridge bank—Novo Banco—was hastily assembled, taking with it senior (non‑subordinated) bonds that initially looked safe.

29 December 2015: The Late‑Night Re‑Transfer

After markets closed on 29 December 2015, BdP ordered five series of senior bonds—worth roughly €2 billion—back to the “bad bank” BES. No warning, no appeal. Global investors such as BlackRock, Pimco and Goldman Sachs saw their rights erased overnight.

The “Saved” Under €100,000

BdP limited the re‑transfer to bonds with a €100,000 minimum denomination, shielding retail savers (who rarely bought such large lots) and avoiding a political storm (perhaps fearing that small savers would take to the streets with pitchforks).

Plaintiffs say that distinction violated the pari passu rule and proportionality principles: creditors of the same class must be treated equally unless a public‑interest reason justifies otherwise—an explanation BdP has never provided. In general, the Noteholders argue that shuffling liabilities from Novo Banco back to the defunct BES wasn’t just a bureaucratic maneuver—it was outright illegal. Apart from the pari passu rule, they allege a string of violations: breach of the applicable statutory requirements pursuant to the Portuguese law to retransfer debts within the resolution of banking entities, breach of the criteria set out in the BRRD to exercise the retransfer power and breach of the criteria set out by the Bank of Portugal itself as many non-qualified investors were also affected by the resolution.

Justice at a Standstill

The first lawsuits date to 2016. For years: nothing. Only in 2024 did Lisbon’s court bundle 37 actions and select four pilot cases. On 2 June 2025, the judge skipped hearings and opted for a preliminary ruling—proof. The Noteholders requested unsuccessfully to file post hearing briefs or to discuss their positions orally given the considerable time passed since the main memorials were filed. A wish to speed things up on the part of the Portuguese justice or to still shies from confrontation?

Breaking Lisbon’s Bottleneck: Bondholders Take the BES/Novo Banco Battle Global

The bondholders didn’t just pack their briefcases for Lisbon’s Administrative Court; they booked long‑haul. Within weeks of the 2015 midnight “re‑transfer,” BlackRock, PIMCO & co. were already threatening a sprint to Strasbourg, branding the move an expropriation fit for the European Court of Human Rights. When Lisbon kept dragging its feet, the money headed for London: first a bruising skirmish over the planned Lone Star sale, then the twin body‑checks of the UK Supreme Court’s Goldman/Guardians defeat in 2018 and the High Court’s 2019 Winterbrook strike‑out. Yet the exodus didn’t stop—Silver Point spun the claim into an investor‑state missile at ICSID, where a tribunal is still ticking over procedural orders in 2025. Bottom line: the creditors have learned to bypass Portugal’s clogged legal arteries by exporting the fight, jurisdiction by jurisdiction, until someone finally pays.

NCWO: No Creditor Worse Off—A Broken Promise?

Investors who did not sue pinned hopes on the NCWO safeguard. A Deloitte study for BdP calculated senior creditors would recover at least 31.7 % in liquidation. Yet after the re‑transfer they received zero, and BES’s 2023 liquidation confirmed nothing would be distributed. When bondholders claimed the 31.7 % plus interest, BdP tried to block them with procedural hurdles and statutes of limitation arguments. Pettifogging sophistries you’d expect from a private adversary—not from the state, whose conduct here is ethically troubling.

Ratings That Missed the Real Risk

Within days of Novo Banco’s birth, rating agencies moved:

- DBRS (7 Aug 2014): BB (low) / R‑4, Under Review – Developing

- Moody’s (13 Aug 2014): B2 deposit rating; senior unsecured at B3, both Review for Downgrade

The ratings were already “junk,” yet none captured the most significant threat—the glacial pace of justice. The Novo Banco saga shows that if authorities can void bonds and courts delay for a decade, legal risk erodes capital faster than any solvency ratio. The time has come for rating agencies to adjust their models.

Trust Without Justice?

Novo Banco is a litmus test for European justice: ten years, zero judgments, investors left empty‑handed. Portugal is not alone; Switzerland’s Credit Suisse AT1 holders are still waiting more than two years after a 48‑hour wipe‑out. David versus Goliath. With one aggravating factor: Goliath sometimes wears a judge’s robe.

Moral 1: Erasing billions can be done in two days; deciding its legality may not be possible in two, five, or even ten years.

Moral 2: States that raid savers’ money count on silence, then oblivion, while slow courts wear down plaintiffs until only nominal “fruit & veg” settlements remain. Thank you—but no. We removed that ring from our noses long ago.

Madrid, Spain, Lugano, Switzerland, Antigua and Barbuda, London, United Kingdom

I don’t involve myself in money people problems. I’m a hundredier and they have far too many 0’s in their money for me to bother myself with their problems

The principle of pari passu was clearly violated in this case. It’s a grave injustice that these senior bondholders were singled out. Their losses were immense and unjust.