An on-going inquiry in the UK has seen the government agree to offer £100,000 in compensation to innocent victims, but whilst being welcomed by some, it has left others frustrated and determined to fight on for justice for grieving families, who continue to be overlooked.

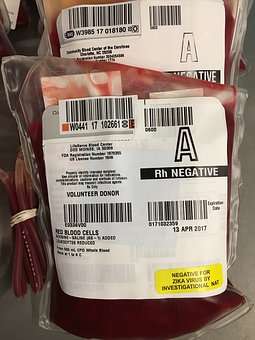

It all centres around what has become known as the “Contaminated Blood Inquiry” which involves thousands of NHS patients, who were infected with HIV or hepatitis C, by imported blood products back in the 1970’s and 1980’s, in a scandal that has since been labelled the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

Many people sadly lost their lives, and those that survived had their lives ruined, and decades of campaigning, amidst continued government denial of responsibility, sparked the launch of the inquiry in July 2018, and which is not due to conclude until some time next year; but an interim report has just been released.

What is the background?

Back in the seventies and eighties, people with haemophilia and similar bleeding disorders, used to receive injections containing blood products to help their blood to clot. During this time it is believed that as many as 5,000 patients were infected with HIV and hepatitis C through contaminated blood products, which had been imported into the UK from America, and almost 50% of that number sadly lost their lives as a result.

The treatment – known as clotting agent Factor VIII – had been introduced to stop the need for patients facing lengthy stays in hospital whilst receiving transfusions, and the demand was significantly higher than could reasonably be supplied from within, so imports were seen as the logical solution. However, a great deal of the human blood plasma which was used came from donors such as prison inmates and drug users, who actually were allowed to sell their blood at that time, hard as it is to believe in today’s environment.

The blood products were then made by pooling plasma from up to 40,000 different donors and concentrating it. It seems incredible to believe such practices were allowed back then, but knowledge was far more limited fifty or so years ago, and what seems foolhardy now, probably never caused particular concern back then. Unwittingly, innocent people requiring blood transfusions after operations, or even after childbirth, were exposed to contaminated blood and it is thought that upwards of 30,000 individuals may have been infected.

By the mid-eighties, it had become clear that HIV was blood-borne, so the products then began being heat-treated, to kill off viruses, but sadly the damage had already been done, and worse still, despite apparent precautions being introduced, some of the contaminated blood remained in circulation and continued to be used, well after this time.

An independent study commissioned by the government, agreed with long-term campaigners, that there had been incompetence and recklessness at play back then, and that victims should eventually be compensated for physical and social injury, the stigma of the disease, the impact on family and work life, and the cost of care. It recommended partners, children, siblings and parents of those who had been infected should be eligible for payments too.

Numbers and statistics

At least 2,400 people died as a result of the contaminations, although it is thought that the number is actually closer to 3,000. Also the early estimate of 5,000 infections is now believed to be some way off a truer figure of nearer 30,000. According to the campaign group “Tainted Blood” out of approximately 1,250 haemophiliacs infected with both hepatitis C and HIV, due to what has been called the biggest scandal in NHS history, fewer than 250 are still alive today.

What exactly is being offered?

Sir Brian Langstaff, who is the chair of the on-going inquiry, recommended immediate interim compensation payments of £100,000 for all surviving victims and bereaved partners of those who had died, due to the “profound physical and mental suffering”, that they endured, as a result of these contaminations. The fact that the government has agreed to meet this recommendation seems to suggest that liability has finally been accepted, although nothing has yet been made official.

It is thought that around 4,000 people are in line for this compensation, with Kit Malthouse, the cabinet office minister, suggesting it would be towards the end of October when the sums of money would reach those to whom it is due: “The infected blood scandal was a tragedy for everyone involved, and the Prime Minister strongly believes that all those who suffered so terribly as a result of this injustice, should receive compensation as quickly as possible” he promised.

This will be the first time that the government has agreed to a compensation payment for things such as loss of earnings, care costs and other lifetime losses, and they have pledged that it will be tax-free, and importantly it will not affect any other support payments that these people might be receiving.

Individual accounts

Ros Cooper was infected with hepatitis C as a child after being diagnosed with a bleeding disorder in 1975. She had no idea for the first 19 years of her life. “It has affected everything, both my physical and my mental health. I was unable to continue working, I have been unable to have children because the treatment for hepatitis C rendered me infertile. It has affected my marriage, it has affected my parents and it has affected my brother and it still affects me now.” She also explained that there is a very real possibility that the damage inflicted by the hepatitis to her liver could lead to her developing cancer in the future. She added that she felt “incredible guilt” over the people who had not been included in the current payment package. “There’s an awful lot of people who haven’t had their suffering recognised.”

Gary Webster, who was eighteen when he was diagnosed with HIV after receiving blood products as a child to treat haemophilia, said his whole life has been changed as a result of being given contaminated blood. “It has affected relationships, my work and my finances. I had to give up work in 2012. I have struggled ever since. I still have a mortgage and I have excessive debts,” he said.

“This money will help with that, but it will not replace what I have lost; but I am one of the lucky ones, because I am still here.”

Andrew Evans, now aged 45, was infected through haemophilia treatments at the age of five with HIV and hepatitis C and developed AIDS at the age of 16. He responded to the announcement of an interim payment by breaking down the payment: “Obviously, it is a very welcome sum of money, however, if you split £100,000 over 40 years of being infected, it works out at just £2,500 a year, which doesn’t really scratch the surface of what I and others have been through.”

Who misses out?

Children who lost parents and parents who lost children have at this point, not been acknowledged and miss out on this initial interim payment. Campaigner Sue Threakall, lost her husband in 1991 after he contracted hepatitis B and HIV from contaminated blood. She vowed to continue to campaign for those left out of the first compensation announcement. “This is not just about money; it is about recognition of people whose lives have been destroyed, young adults have grown up their whole life without their parents and they have not been recognised, and parents whose young children died in their arms. They must be compensated, so we will fight on for them.”

Lauren Palmer, 38, lost both her parents to the scandal when she was just nine years old. Her father Stephen, was given Factor VIII and died of AIDS in August 1993. He had innocently infected her mother, who died in the same month. She said: “How can they have this differentiation and create a hierarchy between bereaved families? I mean all their lives matter just as much as the next person. I have not been able to lead a normal life of having two parents for support.”

This is a victory a long time in the making for some, albeit many decades too late; but for many others who have suffered as much or in some cases even more, they are still awaiting some form of recognition and compensation.

How exactly did this happen?

The contaminated blood scandal has been called the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS. With the factor products being made in huge vats from the plasma of tens of thousands of people, it only needed one donation to be infected and that would be enough to contaminate the whole batch. Warnings about imported Factor VIII had been raised right back in 1974, and the government of the time had committed to making the UK self-sufficient in factor concentrates within three years; but sadly like many government promises, it simply did not happen.

Then as the Aids crisis exploded in the early 1980’s, the Department of Health was warned again in writing that US blood products should be withdrawn from circulation, but it wasn’t until 1986, an astonishing twelve years after concerns were first raised, that this was advice was finally observed. Screening of all blood products began in 1991 and by the end of the decade synthetic treatments for haemophilia became available, removing the infection risk; but unfortunately the metaphorical horse had long since bolted after this particular door was finally closed.

Previous denials

Survivors have accused ministers of misleading the public by playing down fears of infection.

The first reliable blood test for HIV was only available in March 1985, after many haemophiliacs had already been infected with the virus through Factor VIII.

A quote from Ken Clarke, later to become Lord Clarke, serving in the government during the eighties, summed up the government stance at the time: “It has been suggested that Aids may be transmitted in blood or blood products, there is no conclusive proof that this is so.” But he told the inquiry back in 2019 that he in no way was responsible for any part of the blood scandal. He suggested that the government needed to balance the risk of contaminated blood products with the danger of creating a “panic” which might have put people off donating blood, or proceeding with an operation. Basically, walking away from shouldering any blame.

Jason Evans, whose father Jonathan, died of Aids in 1993 said: “If the government had told the full truth of what was happening a year before, there is a very strong possibility that my Dad would be here today.” He added: “Clarke has no respect for this inquiry, or anyone involved in it. I cannot begin to convey the sense of frustration and anger the victims and families feel towards him.”

Support from former health secretaries

Labour’s former health secretary Andy Burnham and two of his Conservative successors: Jeremy Hunt and Matt Hancock, had called on the Prime Minister to authorise payments straight away. In a joint letter they wrote: “As health secretaries with a combined period in office of 10 years, we passionately believe that this is the vital next step towards justice for those who have suffered dreadfully over the decades as a result of this scandal.”

They went on to stress: “By arguing that we need to wait for the inquiry to finish, for a new Prime Minister to be appointed, or for parliament to return, is ignoring the fact that over 400 people had already died since the inquiry started and a hold up would sadly almost certainly see more of the victims die before they see any justice.”

Prime Minister’s message

Boris Johnson said: “While nothing can make up for the pain and suffering endured by those affected by this tragic injustice, we are taking action to do right by victims and those who have tragically lost their partners, by making sure they receive these interim payments as quickly as possible. We will continue to stand by all those impacted by this horrific tragedy, and I want to personally pay tribute to all those who have so determinedly fought for justice.”

Have people been infected elsewhere in the world?

The UK are not alone in this scandal, it is just that they are one of the last to take ownership of it. There have been tens of thousands of cases of people being given infected blood not only in the US, but also other countries who also imported blood products during the 1970s and 1980s. In Europe, there have been cases in France, Italy, Ireland, and Portugal; together with the likes of: Canada, Iran, Iraq and Japan.

In the States, the companies which supplied the infected products have been forced to pay out millions of dollars in out-of-court settlements. Elsewhere, politicians and drug companies have been convicted of negligence. At the opening of the UK inquiry, it was announced that criminal trials could easily follow, if shortcomings are uncovered, and individuals can be identified with even part culpability.

When will the inquiry end?

The UK-wide inquiry was launched after years of campaigning by victims and their families, who claim the risks were never properly explained and the scandal was one big cover up. It has been led by former judge Sir Brian Langstaff, who has given his preliminary recommendations in an interim report, but the inquiry continues and is not expected to finish until the early part of 2023.

It is hoped there will be some accountability at its conclusion, as well as compensation awards for a wider group of deserving people. It is thought the final bill could cost the government in excess of £1bn.

0 Comments