You can now listen to Antigua News articles!

Parliamentary Reform is Overdue

By Kieron Murdoch | Opinion Contributor

Antigua and Barbuda will mark 43 years of independence this November, celebrating the achievements of its people and the relative strength of its democracy. The season has always been one of reflection on issues that define our nationhood, and not solely one of celebration. These are issues like socioeconomic progress, equal rights and opportunities for all, and the strength of national institutions.

We perhaps need to spend a little more time focusing on that last issue specifically. We should start with our Parliament, which theoretically ought to sit at the apex when considering all our national institutions. Our trouble has been and continues to be that we have never had in our Parliament, an exemplary assembly by any means, and we have fallen into the malaise of being at peace with things as they are.

We do not however, often acknowledge the limitations of our Parliament, and while many citizens know that Parliamentarians represent them, too many may be hard pressed to delve further into the ways in which that representation ought to occur, or into the mechanisms and customs that ought to fine tune the workings of a good assembly.

We seldom hear elected members of parliament (MPs), senators, or political hopefuls discussing the mechanics behind political institutions in our country. They tend to focus on bread and butter issues, and not on debates about the functionality of institutions. Additionally, and most unfortunately, we have not historically had the benefit of a robust press, civil society, or academia, willing to discuss such topics with the level of seriousness and frequency they warrant.

A legislature in a parliamentary democracy with a ministerial government such as ours, ought to execute at least these functions: representation, deliberation, legislation, and oversight. These functions are not exhaustive. A democracy is premised on the idea that the people hold power. For practical reasons, that power is exercised through periodically elected representatives, as opposed to holding direct popular votes on each proposed law and policy.

Parliament should therefore be representative, meaning that the people’s interest ought to be championed by their MPs at all times. Political parties are a natural part of the electoral and representative process and allow us to unite around shared agendas, ideas and principles. Having political groups represented in Parliament is necessary, but it is the people to whom allegiance is first owed.

In its deliberative function, Parliament ought to be a body where issues of societal importance are debated genuinely, transparently, and publicly. A parliament’s involvement in the legislative process varies from country to country, however, in models like ours, it is accepted that the executive proposes legislation and drives the legislative process forward. Nevertheless, the legislative function of parliament entitles it to accept or reject executive policy according to the convictions and agendas of MPs who ought to represent the people. MPs therefore ought to be very much involved in the legislative process through procedures which will differ in different systems.

Oversight is perhaps the most overlooked role of legislatures in countries such as ours. It is, however, a fundamental role of any legislature. The power to make law and to accept and reject executive policy must be used to make demands on the executive for accountability, honesty, transparency, integrity, and good performance in office.

But our parliamentary system as it is today, is a misfit, chiefly because it was meant for nations where there are far more constituencies and far more members in Parliament. Remember that our model evolved in vastly larger democracies before it was adopted by us for democratic governance.

The model divides the national territory into single seat constituencies and the elected representatives from each constituency come together to form the legislature. Amongst them, a leader – the Prime Minister – will be selected to run the executive branch. He or she will add other MPs to the Cabinet and together they run the executive branch collectively.

But in the large democracies such as Britain, where the parliamentary system developed, there are literally hundreds of constituencies and hundreds of MPs. That means that a Prime Minister and their Cabinet were always a small subgroup within Parliament. It meant that a Prime Minister and their Cabinet had to continuously seek the support of Parliament’s MPs to get laws passed, get policy approved, and for Parliament to retain confidence in that Prime Minister’s leadership, and confidence in the ministers they appointed.

Cabinet sizes vary from country to country. Some can be as small as 7 members (Switzerland) or as large as 29 members (India) or even more. In the larger democracies, after a Prime Minister has nominated some MPs from their party to join them in forming the Cabinet, there are still many, sometimes hundreds of other ruling party MPs left back who are just ordinary MPs.

These are referred to as backbenchers, because in the traditional seating arrangements of parliaments – especially those which take their cue from Britain – the MPs who are ministers sit up front, and the many more MPs who are not ministers sit on the benches behind them – backbenchers.

On the opposition side, a Leader of the Opposition is designated, and that person is able to nominate what is traditionally referred to as a Shadow Cabinet. These are opposition MPs who have been designated to keep track of the activities of different Cabinet ministers and their departments, and to take the lead in demanding accountability from those ministers and their departments. This group traditionally sat on the front bench on the opposition side, and opposition MPs who are not in the Shadow Cabinet sat on the benches behind them – also backbenchers.

In order to be more efficient and targeted in handling its affairs, a Parliament traditionally then divides itself into various permanent committees. A committee will be designated certain areas of policy for which it is responsible. It would traditionally have the power to make enquiries of the executive branch as relates to the handling of issues related to those areas of policy. It may also have power to debate legislation related to those areas of policy before that legislation is finally voted on by the whole house. Committees are a very basic element of parliamentary governance.

Thus far, we have established four characteristics of Parliaments which are often taken for granted in larger democracies. Firstly, there is a vast numerical superiority of ordinary MPs over the MPs in the Cabinet. Secondly, there is a backbench of ordinary MPs who are members of the ruling party, and this group also tends to be larger in number than the Cabinet.

Thirdly, there is a Shadow Cabinet, and by implication, there are enough opposition MPs to form such a Shadow Cabinet. Fourthly, there are parliamentary committees empowered to oversee enquiry and debate on different areas of policy on parliament’s behalf, which implies that there are enough non-Cabinet MPs to sit on these committees – it would be preposterous to have Cabinet MPs (ministers) dominate parliamentary committees to oversee and enquire into their own performance.

Now we run into the problem. When you transpose this system onto a small island state like Antigua and Barbuda, you run into the immediate dilemma of not being able to divide up the national territory into many constituencies. The system evolved in a Parliament with hundreds of MPs. We have just 17. With such a small number, and with any Prime Minister’s need to find MPs to put in his or her Cabinet as ministers, almost every MP from the governing party invariably becomes a member of the Cabinet. That is a problem.

Cabinets in our system and in similar systems across the Caribbean have long emerged as the numerically dominant group in the parliament, being fully capable of passing legislation without the support of any other MP in the assembly.

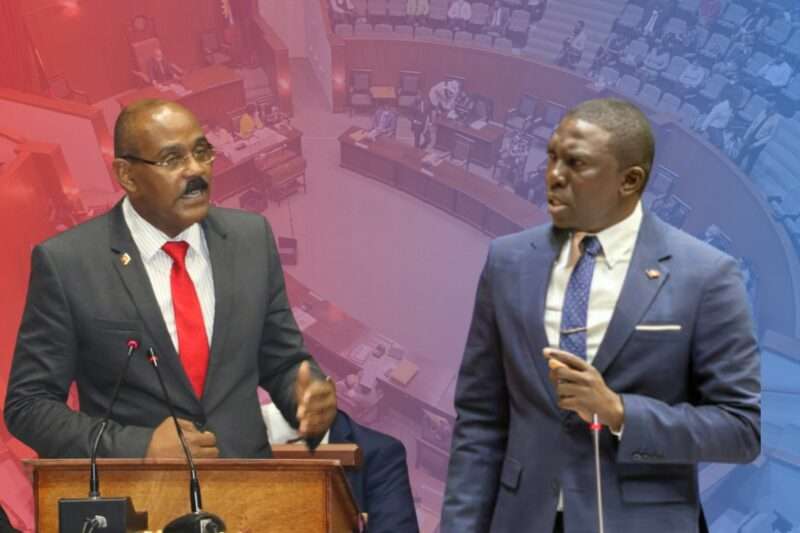

For example, between 2018 and 2023, the Antigua and Barbuda Labour Party (ABLP) held 15 of 17 parliamentary seats. At one point, 14 of those 15 Labour MPs were in the Cabinet. Between 2009 and 2014, the United Progressive Party (UPP) and Barbuda People’s Movement (BPM) together held 10 of 17 parliamentary seats. Of this number, 9 were made ministers.

It has traditionally been numerically impossible for the Cabinet in our context to lose the confidence of parliament. It is numerically impossible for them to lose a vote on any bill. It is impossible for them to be censured by the house in any way whatsoever as long as they always vote in the house as a unit, which they are bound by the convention of collective responsibility to do.

However, if a government is unencumbered by the threat of legislative censure, the failure of a Bill, or votes of no confidence, it will become far less circumspect in how it manages state affairs. This effectively makes going to the Parliament a formality. In the five years between elections, there is no one with the formal power to tell a government “no”.

Remember those four very simple things we identified earlier about traditional Parliaments as they had emerged in larger democracies? Not one of those things is present in our system. Not one. Firstly, the numerical superiority of ordinary MPs over the Cabinet has never been a feature of our parliamentary system. Secondly, the ruling party never has a substantial back bench of ordinary MPs who are not in the Cabinet.

Thirdly, the existence of a Shadow Cabinet has never been a guaranteed standard, as there are hardly ever enough opposition MPs to form a full one. Even when there is one in name, in political practice, it is under-resourced and its members hardly treat it as though it were as serious a responsibility as it ought to be. Fourthly, the existence of parliamentary committees to oversee ministerial and departmental activity has never been a norm. Often, there are too few MPs outside the Cabinet to form such committees.

On the issue of backbench MPs – these are vital to the functioning of Parliament, especially on the ruling party’s side. As they hold no executive position, they are not beholden to the Prime Minister or the Cabinet for their post. They are more inclined to speak honestly about issues facing the nation and facing their constituents.

As an example, consider how often Dean Jonas reprimanded the government for poor performance when he was the sole Labour backbencher for several years after 2014 and prior to 2018. Where was that fire when he was in Cabinet till 2023? It would be improper for him to have done so as a Minister later on, since he was collectively responsible for fixing the same problems of which he was previously so critical.

That is the role of the government backbench – to be a reality check to the Cabinet and to make the Cabinet answerable to their own party in Parliament. We have no such backbench. And with no Shadow Cabinet, the opposition is drastically less organised in how it responds to all that the government does.

Additionally, with so few seats, representation often becomes skewed and parliamentary opposition can be eliminated entirely. The latter very nearly happened here in 2018, as it had happened in Grenada and would later happen in Barbados the same year.

Here, The idea that one party could win all the seats in the Parliament has never been a threat in the larger democracies where parliamentary systems evolved. In the UK, there are 650 seats. It would be unthinkable for any party to seriously hope to win all of them. There are innumerable “safe seats” on either side in these larger examples. But there are no safe seats in our context.

Our electorates are small. There are no obscure regions where the people have only ever supported one party. All of our seats can be swung. Since it must be said, we will say it: There is something fundamentally wrong with a system which bears the inherent risk of the elimination of all opposition from the Parliament.

And yet, in spite of that, we have carried on with this system without fundamental improvements and largely without meaningfully acknowledging its drawbacks. It brings us to the point upon which we will conclude part one of this discussion, and that is that our awareness that something is wrong is limited by the extent to which we fully comprehend that a better way exists. Once we remain unaware, we are more inclined to treat that which would otherwise be unacceptable as acceptable.

For instance, were a person to have only ever consumed dry and unseasoned jerk pork, they might be forgiven for reaching the mistaken conclusion that it was an inherently unappetizing dish. Similarly, were a person to be accustomed only to works and infrastructure in Antigua and Barbuda, they might be forgiven for concluding that sidewalks and roads are for the most part, mutually exclusive phenomena.

Consider this anecdote inspired by the actual experience of one of our staffers at antigua.news. A visitor is being driven down Old Parham Road by a resident who has lived in Antigua their whole life. “Why is this big open gutter running along this main road?” the visitor asks. The resident does not have an answer. Till then, the resident had never questioned it – not even briefly. In the decades they had been alive, the gutter had been exactly where it was, exactly as it was, for as far back as the resident’s memory served.

Yet, the gutter seems anomalous to the visitor. They are perhaps wondering, why is a bustling main road dotted with shops, restaurants, supermarkets, dealerships, business centres and a bank, complimented by a large, uncovered, concrete, v-shaped trench gutter running parallel to the said road, occasionally being choked with bush and moss, and from time to time being mildly odorous?

Something which is inherently flawed can persist without the acknowledgement that it is flawed because we, the observers, have never known it to be any better. Despite what fundamental flaws become appallingly obvious upon closer inspection, it may remain acceptable so long as we have no sense of what it ought to be compared to.

About the writer:

Kieron Murdoch worked as a journalist and later as a radio presenter in Antigua and Barbuda for eight years, covering politics and governance especially. He is an opinion contributor at antigua.news. If you have an opinion on the issues raised in this editorial and you would like to submit a response by email to be considered for publication, please email staff@antigua.news.

0 Comments