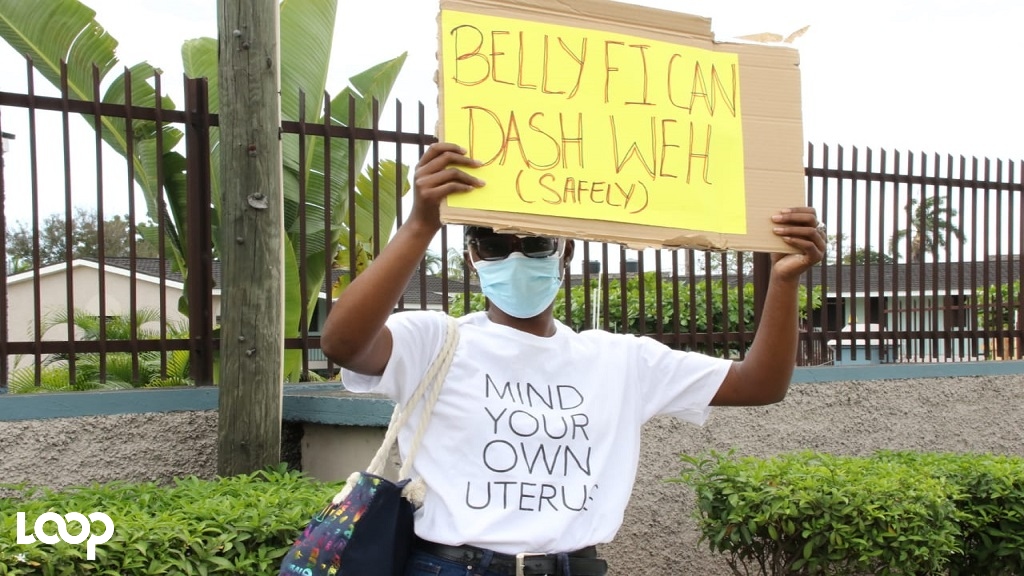

Yes to Safe and Legal Abortion

By Kieron Murdoch | Opinion Contributor

A woman in Antigua and Barbuda who has a pregnancy she does not wish to carry to term ought to have legal and safe access to an abortion should she wish it. That is the stance which has compelled a group of activists on the issue of women’s access to abortion to challenge this country’s restrictive abortion laws in court. It is a stance with which we agree.

To begin, what is an abortion? An abortion, also known as a termination of a pregnancy, is the removal or expulsion of a human embryo or foetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage. An induced abortion – the subject at hand – is a procedure to end a pregnancy and is what is usually being referenced by the use of the word abortion. It can be done through use of medication or through a medical procedure.

At least two Acts criminalise abortion in Antigua and Barbuda. The first is the Offences Against the Person Act CAP 300, Sections 56 and 57 of which state that it is unlawful for a woman “to procure her own miscarriage” (to have an abortion) or for anyone to assist in that regard. The maximum penalty provided is 10 years in prison with or without hard labour.

It is also unlawful under this Act to knowingly supply medication or instruments for abortion, the penalty being a maximum of two years in prison with or without hard labour. This Act has been in force since sometime 1861 or thereabouts. Lawyers for the government recently noted that it was included in a list of sections repealed by the passage of another Act in 1995 – something which is expected to be further debated during a case now challenging the law.

Meanwhile, the other Act, the Infant Life Preservation Act CAP 216, in force since 1937, creates an additional offence called “child destruction” which is to “cause a child to die before it has an existence independent of its mother”. The Act introduces the concept of “a child capable of being born alive” and stipulates that this applies to a foetus at 28 weeks of pregnancy (around 6.5 months) and thereafter.

The exception provided is where termination at 28 weeks or thereafter was done “in good faith for the purpose only of preserving the life of the mother”. In short, abortion at 28 weeks and thereafter is a separate offence under the Infant Life Preservation Act for which the penalty is prison for life with or without hard labour – a noticeably harsher penalty than the offence of “procuring a miscarriage” as discussed in the Offences Against the Person Act.

So, the first Act appears to make abortion illegal outright, with no exceptions, at any stage of pregnancy. The second Act appears to make abortion at 28 weeks or thereafter a separate, unique, and even more severe offence, which attracts a harsher penalty, unless it was done to preserve the life of the mother.

The second Act also makes it permissible for a jury to convict a person of the alternate offence in any instance where such a person was on trial for either offence and was found not guilty. For example, if a person were on trial for “procuring a misscarriage” under the Offences Against the Person Act, and they are found not guilty, they may yet be found guilty of “child destruction” under the Infant Life Preservation Act if the evidence proves this. It applies vice versa.

Understanding what the law states, we must examine the prevalence of abortion in Antigua and Barbuda despite the law. Advocates for Safe Parenthood Improving Reproductive Equity (ASPIRE), the group which is presently challenging the anti-abortion provisions of the Offences Against the Person Act in court, took the time to do a number of surveys examining that.

In June 2024, the Observer spoke to ASPIRE’s Dr. Fred Nunes (PhD) about the research. He revealed that a recent survey suggested that “72 percent of women in Antigua will have an abortion by age 44”, and that support for broadening abortion access was strong among healthcare professionals – as much as 78 percent. He emphasised that women from worse socioeconomic circumstances stood to benefit most from safe and equitable access to abortion.

In May 2022, Loop News published an article discussing the subject of how accessible abortion pills are in Antigua and Barbuda. The outlet quoted a then 36-year-old woman in Antigua who said: “You simply go to one of the pharmacies that sell them and walk straight to the pharmacist and ask for it. The pharmacist will ask you how far along you are because you shouldn’t take it if you are more than 10 weeks.”

“The pharmacist may ask you other questions too like if you’ve ever done an abortion before but once everything is fine you will be given another pill to purchase such as painkillers and when you go back to the pharmacist to collect it, he will give you the abortion pills and explain what to do and you pay $350 plus whatever you paid for the painkillers,” she stated.

At this stage, you would be right to wonder how many people are currently in prison for abortion, which brings us to the issue of the enforcement of these laws. It is either minimal or nonexistent. That is not surprising however, as the people who enforce our laws tend to take their cues from society. After all, they are products of society. Their interest in taking action on this issue or that is often, though not always, a reflection of our general attitude and that of our elected leaders on the severity of a crime (or lack thereof).

Were there crowds clamouring in the street for women to be arrested and imprisoned for having abortions, or were a government to demand of the police the full and unrestrained enforcement of such laws, then it would not be surprising if law enforcement took a greater interest. But whilst neither the people nor the government are interested in enforcement, it appears law enforcement will take a similar approach.

Like the recently stuck down anti-buggery provision and the issue of human rights for LGBT people that it represented, the anti-abortion law represents an issue (abortion) that exists in a sort of sociocultural stasis on the spectrum of social progress. Moving it forward means repealing the laws and adopting new laws to support safe and equitable abortion access.

Moving it backward means not only keeping it on the books, but going a step further to actually enforce the provisions. The reason we say it remains in stasis is because the progressive current in our society cannot move the issue forward without sparking confrontation with those of more conservative views, but neither are the more conservative able to pull it back without igniting push back from the more progressive.

An unenforced law serves little purpose other than being a statement of society’s moral position. In this case, it is an evidently false statement which does not accurately represent the changed views of society of whether abortion should be criminalised, but one which serves to appease those who sermonise tediously about our gradual slippage into a moral abyss, and the inevitable fire and brimstone which such slippage invites.

Yet, despite being unenforced, the law does have an impact. Yes, people access abortion in Antigua and Barbuda. Both medication-induced and procedural abortion are available to women who know where to go. However, the fact that it is unlawful prevents there from being an open, well regulated, and transparent medical and administrative infrastructure around it to enhance its safety and the equity of access to the service.

What are the national criteria that govern its safety? Who regulates whether this person or that person is qualified to perform a procedure? Who regulates whether this person or that person is authorised to distribute the abortion pill? How are insurance providers to deal with this and any related procedures or care if abortion is illegal? How can its cost be made affordable if it remains essentially a black market service?

How does a woman who is experiencing any level of psychological distress due to an unplanned pregnancy and her decision to terminate it, confidently seek support in circumstances where the act of termination was a crime, and where the law against abortion serves to embolden the pious in the quest to stigmatise her?

We imagine that these might be among the various concerns that prompted ASPIRE to challenge the issue of abortion’s criminalisation in court, which brings us to the issue of the ongoing effort to change the law. ASPIRE has asked the court to overturn Sections 56 and 57 of the Offences Against the Person Act which deal with abortion. At a recent hearing, a judge decided to let the case go ahead to a trial despite a request by the government to have it struck out prior.

Interestingly, the government has now argued that Sections 56 and 57 have not been in force since 1995. They pointed to repeal provisions at the end of the Sexual Offences Act 1995 which included these two abortion-related sections among a list of other sections of the Offences Against the Persons Act, and argued that ASPIRE’s case should have focused on the Infant Life Preservation Act instead.

ASPIRE’s lawyer argued that Parliament could not have intended to have repealed the abortion laws in an Act that solely addressed sexual offences. The judge took the position that the case should go to trial where further arguments could be properly heard. However, the point raised by the government’s lawyers has added another controversy to the mix.

If you go to the Sexual Offences Act 1995, you will in fact notice at the end that it lists Sections 46, 47, 48, 49, and 50, as well as 56 and 57 (abortion provisions) of the Offences Against the Person Act as being repealed. A number of questions arise. Why were these two provisions included when they had nothing to do with sexual offences? Was this just an error?

Was Parliament aware that they had passed legislation listing unrelated sections for repeal? Was it the government’s intention at the time to sneakily repeal the abortion provisions without Parliament noticing or debating the subject? Or was it a genuine error that the government’s lawyers are now leaning on to try and stymie the case?

Go back to the Offences Against the Person Act, and you will note that not only do Sections 56 and 57 (abortion provisions) have nothing to do with sexual offences, but neither do three of the other repealed sections, Sections 46, 47 and 48. They have to do with assault and battery. Was this intentional? Introducing this has only raised more questions about how Parliament has dealt with drafting, review, repeals, amendments, and codification over the years.

If we accept the stance of the government’s lawyers on this particular point, it would mean that the only anti-abortion law in force in Antigua and Barbuda is the Infant Life Preservation Act, which would mean that abortions here are permissible prior to 28 weeks (6.5 months), as Sections 56 and 57 of the Offences Against the Person Act would have been repealed, thus eliminating the carte blanche criminalisation of abortion.

All abortions are legal up to 28 weeks? When have you ever heard the government suggest this to be the case? It should be noted that at no point in the past few years has the Attorney General ever suggested anything of the sort. The fact that this ambiguity has been introduced at this stage must be taken as a display of the lack of seriousness with which the government has treated this matter.

That brings us to the issue of the government’s position on the subject. It has none. The government’s position is to avoid the ire of the Church and to avoid what it sees as the unnecessary risk of placing itself at the centre of what will certainly become a divisive political issue should it go the route of debating the repeal of the anti-abortion laws in Parliament.

The government, represented here by the Attorney General, the Hon. Sir Steadroy Benjamin MP, has demonstrated political cowardice on the subject matter, dancing on the line between sounding as though it supports greater access to safe abortion, and sounding as though it does not care to upset the status quo. It struck a similar tone on the anti-buggery laws which it also refused to repeal, preferring instead that the judicial branch be castigated by the clergy rather than the executive.

It is not at all surprising that the move to try and have another morally contentious but unenforced law struck down has stirred up some of the nation’s faith leaders. This brings us to the issue of the influence of the Church. The Church still holds great sway in Antigua and Barbuda although many institutions complain still of their declining numbers. Nevertheless, even those who do not frequent the pews on Sundays or Saturdays may be quick to join the throng when a moral position is espoused by a faith leader on some contentious social issue.

The government’s fear of the organised Church and the latent power it holds to stir up the people against the administration is constantly evident. Regardless of whether we are speaking of human rights for LGBT people, access to abortion, use of corporal punishment, criminalisation of martial rape, sex education in schools, or selling alcohol on Good Friday, it seems at times that progress must be forever hostaged to the whims of a few pious old men.

In June 2024, Loop News reported that the president of the Antigua & Barbuda Evangelical Alliance (ABEA), Rev. Dr. Olson Daniel, was urging the government to resist calls to decriminalise abortion, saying, “What the bible says is what we should live by and that is that somebody is not just somebody when they are born, they are formed in the womb”.

What faith leaders tend not to acknowledge is that the status quo is already one in which society is willing to accept that abortion is accessible, just not legally. That means that in keeping the law in place, they are either asking us to keep the status quo and that abortions should remain less safe, less accessible to poor women, and unregulated; or they want us to actually enforce the law.

Enforcing the law would demand that the police round up every married woman who aborted a child, and every teenage girl who has gotten pregnant unintentionally and has gotten an abortion, and every doctor, nurse, and pharmacist who has ever supplied or assisted in the act of abortion, and jail them for up to 10 years with hard labour.

We have so far examined what abortion is, the laws criminalising abortion in Antigua and Barbuda, the prevalence of abortion, the enforcement or lack thereof of the laws concerning abortion, the impact of the laws on women, the efforts to change those laws, the position of the government or lack thereof on the entire subject, and the influence of the Church. We now return to the statement with which we opened: A woman in Antigua and Barbuda who has a pregnancy she does not wish to carry to term ought to have legal and safe access to an abortion should she wish it.

Abortion discussions are essentially moral debates, and the positions of the persons engaged in those debates tend to be entrenched most times, though not always. The debate tends to focus on two issues: a woman’s bodily autonomy and the concept of a right to choose whether or not to carry a pregnancy, and the idea of foetal personhood and the extent to which a foetus at various stages attracts fundamental rights.

While it must be acknowledged that a foetus or an unborn child ought to attract certain rights and protections, it would be untenable to engender a situation where the rights of a foetus carry more weight than those of the mother and of her autonomy. The act of termination should not be taken lightly, but it perhaps a choice best left with the mother rather than restricted en masse.

Protecting this idea of autonomy means making abortion accessible to women legally and safely without fetters that require that they present with specific circumstances like having been the victim of rape, or being in a life threatening situation due to the pregnancy. A married mother of three who did not intend to get pregnant by her husband again, and who does not wish to have another child should have access to an abortion.

Beyond the point about the choice of the mother overriding the rights of the foetus, it seems reasonable to say that non-restrictive access to abortion should be part of any good population management policy. Why make more parents of unwilling and unprepared mothers and fathers? Why not allow them to delay having children by terminating pregnancies which were unplanned and which threaten to derail them? This merely invites more social problems and often aids in perpetuating cycles of poverty.

Safe and legal access to abortion would also create clarity for medical care providers, insurers and the healthcare system. It would allow for the drugs used to be regulated, for the people offering those drugs to be regulated, for the doctors performing these procedures to be regulated and protected, and for the healthcare system to create the right procedures to administer, track, and govern this space. It would make the process safer and less costly for women. Legalising access would also help to remove the stigma surrounding abortion.

Importantly, we should acknowledge that society has long come to the point where it is willing to tolerate abortion without clamouring for the enforcement of the anti-abortion laws. This suggests that most people are at least of the view that a woman ought not be imprisoned – nor should those assisting her – if she chooses an abortion. Recognising this, we ought to ask ourselves, what is the point of maintaining a law which simply makes the said abortion more expensive, less accessible to the poor, less safe, and more stigmatised?

Share your abortion story

Have you ever had an abortion? Write to us about the circumstances that led to the pregnancy and what it was like making the decision to terminate it. How easy or difficult was it to access abortion? What are your thoughts on the abortion debate in Antigua and Barbuda? To protect your identity, you do not have to use your real name. Send your letter to [email protected]

About the writer:

Kieron Murdoch is an opinion contributor at antigua.news. He previously worked as a journalist and later as a radio presenter in Antigua and Barbuda for eight years, covering politics and governance especially.

0 Comments